This doth be a machine-wrought text which may contain errors!

In Python (and ‘tis true of most other tongues), ‘tis possible to create one’s own objects, with values, rules, and functions peculiar unto them. These are called Classes (in the English fashion). We employ Classes to gather related data and functions into a single unit, for example, an Ordre Class which doth hold data such as ordre_id, kunde_navn, produkter, and functions like legg_til_produkt(), beregn_total(), and the like.

Dictionary (JSON) vs Klasser (Objekter)

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) doth be a form for to store and convey data, independent of the tongue of programming, whilst a class is a structure within a specific tongue of programming.

When we would send data o’er the network, or store it within a file, ‘tis oft JSON we employ (or tables within databases).

When we would work with structured data in code, ‘tis classes we do use.

In this module, we shall observe how we may employ classes to validate data.

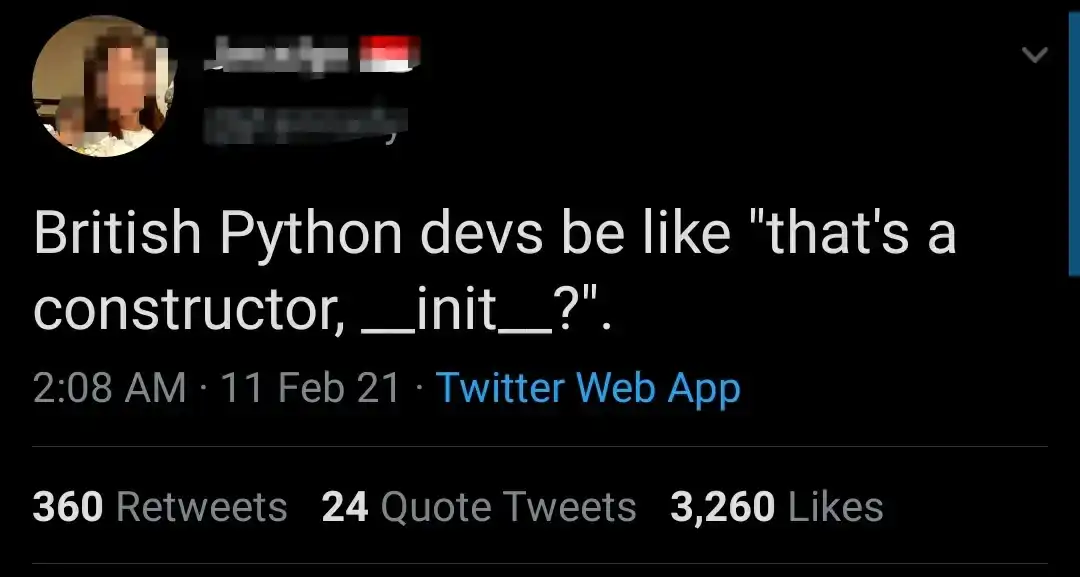

The easiest course is to make use of @dataclass from the dataclasses library. This doth allow us to eschew the writing of much boilerplate code for the creation of a class. (Such as, for example, the built-in __init__ and __repr__ (representation) functions).

An example of a class without employing the dataclass decorator:

class Car:

def __init__(self, make: str, model: str, year: int):

self.make = make

self.model = model

self.year = year

def __repr__(self):

return f"{self.year} {self.make} {self.model}"

my_car = Car("Toyota", "Corolla", 2020)

print(my_car) # Output: 2020 Toyota Corolla # Forsooth, this doth print the car's details.

An Example with the dataclass Decorator, which doth achieve the same as above (but with less Code):

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Car:

make: str

model: str

year: int

my_car = Car("Toyota", "Corolla", 2020)

print(my_car) # Utdata: Bil(merke='Toyota', modell='Corolla', år=2020) # Output: Car(make='Toyota', model='Corolla', year=2020)

Task the First - To Forge a Class

Task the First - To Forge a Class

Forge ye a class hight Person. This class shall possess these qualities (attributes):

name: The name of the personageeye_color: The hue of the person’s eyesphone_number: The person’s number for telephonyemail: The person’s address for electronic post

Instantiate (take into use) an object of the class Person with values meet for all qualities, as in the example hereunder.

@dataclass

class Person:

... # Thy code doth reside here

bob_kaare = Person(name="Bob Kåre",

eye_color="blue",

phone_number="12345678",

email="bob_kaare@example.com")

print(bob_kaare)

Løsning: En dataclass for Person

Here doth lie a possible resolution:

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Person:

name: str

eye_color: str

phone_number: str

email: str

Task the Second – Validation within the Class

Task the Second – Validation within the Class

In the example yclept above, we have not added any validation, good sir. ‘Tis to say, we may fashion a Person with values most unsound, such as:

@dataclass

class Person:

... # Thy code doth reside here

invalid_person = Person(name="",

eye_color="yes",

phone_number="12345",

email="not-an-email")

print(invalid_person)

# Output: Person(name='', eye_color='yes', phone_number='12345', email='not-an-email')

This doth (perchance) present a troublesome matter, and may well accrue technical debt in times to come. Thankfully, there exist simple ways to add validation unto classes.

We shall begin by beholding email validation. There are libraries built within Python which may aid us in this endeavour, but forasmuch as we do this to learn, we shall craft our own simple validation, by creating a new class for “Email”, and examining a __post_init__ function (for dataclass only).

Merk

We may eke do this within the very Person class, yet ‘tis oft better to fashion separate classes for such things as may be reused.

An exemplification of a post_init function

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Email:

address: str

def __post_init__(self):

print(f"Validating email: {self.address}")

# Thine own code doth reside here

For a simple email validation, we may perchance check that the email doth contain both @ and . characters. Peradventure thou mayest also check that the email doth match a regex pattern. (More advanced, yet seek ye upon the web, I pray!)

Løsning: Kode for enkel e-post validering

Here doth lie a possible solution, where we employ exceptions to “crash” should the email prove invalid, thus halting the program forthwith and yielding an error message.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Email:

address: str

def __post_init__(self):

if "@" not in self.address:

raise ValueError(f"Mangler @ i epostadressen: {self.address}")

if "." not in self.address.split("@")[1]:

raise ValueError(f"Mangler . i domenet til epostadressen: {self.address}")

if " " in self.address:

raise ValueError(f"Epostadressen kan ikke inneholde mellomrom: {self.address}")

# Test koden

test = Email("hei@example.com") # Gyldig

try:

test = Email("heiexample.com")

except ValueError as e:

print(e) # Ugyldig, mangler @

Task the Third – Telephone Number Validation

Task the Third – Telephone Number Validation

Create, in like manner as thou didst for electronic missives, a class, but now for telephone numbers.

Challenge with telephone validation!

Prithee, canst thou mend the validation for telephone numbers to accept both letters (str) and numbers (int)? For example, 12345678 and "12345678" should both be valid.

Essay also to add country codes as an attribute (a sub-value to the class). For example, 47 for Norway, 46 for Sweden

Task the Fourth - Employ Validation within the Person Class

Task the Fourth - Employ Validation within the Person Class

Now that we have wrought validation for email and telephone number, we may employ these within the Person class.

@dataclass

class Person:

name: str

eye_color: str

phone_number: PhoneNumber # Prithee, employ the PhoneNumber class

email: Email # Pray, make use of the Email class

A new challenge doth arise!

Now that we have altered the Person class to employ the PhoneNumber and Email classes, we must also amend how we instantiate (create) a Person. We must now first fashion a PhoneNumber and an Email object, ere we may create a Person.

bob_kaare = Person(name="Bob Kåre",

eye_color="blue",

phone_number=PhoneNumber("12345678"), # Hark, a change doth here reside!

email=Email("bob_kaare@example.com")) # Prithee, observe a change doth here abide!

print(bob_kaare)

# Attend! A change must needs be wrought in how we extract the values also

print(bob_kaare.email.address)

print(bob_kaare.phone_number.number) # .country_code(?)

Task 5 - Properties in Classes (Optional)

Task 5 - Properties in Classes (Optional)

When we do employ objects to represent values such as e-mail and telephone number, ‘tis needful we specify the sub-value (for example, address for e-mail and number for telephone number) each time we seek to extract the value. This may become somewhat cumbersome in the long run. Thankfully, there doth exist a solution to this, by the use of the @property decorator within a class, which alloweth us to extract the value directly from the object, without needing to specify the sub-value.

This doth, however, present yet another challenge, and ‘tis that we require the __init__ function within the Person class. This is because we cannot employ the same name for both a property and an attribute within a dataclass.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class EksempelVerdi:

attributt: str

@dataclass

class Person:

name: str

_verdi: EksempelVerdi # An inward variable (doth begin with _ to signify 'tis "private")

def __init__(self, name: str, verdi: EksempelVerdi):

self.name = name

self._verdi = verdi

@property

def verdi(self):

return self._verdi.attributt # Doth fetch the under-value directly

# Test koden

person = Person(name="Alice", verdi=EksempelVerdi("Noe tekst"))

print(person.verdi) # Output: Noe tekst

Merk

Properties be singular in that they require not parameters, nor need parentheses to be run. In the example, we do fetch forth person.verdi without parentheses (not person.verdi()), albeit ‘tis a function technically.

Alternativt eksempel som aksepterer både str og EksempelVerdi

@dataclass

class Person:

name: str

_verdi: str

def __init__(self, name: str, verdi: str | EksempelVerdi):

self.name = name

if isinstance(verdi, EksempelVerdi):

self._verdi = verdi

elif isinstance(verdi, str):

self._verdi = EksempelVerdi(verdi)

else:

raise TypeError("verdi må være av type str eller EksempelVerdi")

@property

def verdi(self) -> str:

return self._verdi.attributt # Henter ut underverdien direkte

# Test koden

person = Person(name="Alice", verdi="Noe tekst")

print(person.verdi) # Output: Noe tekst

Task 6 - Properties with Logic (Optional)

Task 6 - Properties with Logic (Optional)

Update Person by adding a new attribute hight birthday. This shall be of the type datetime.date (from the datetime library).

Thereafter, thou shalt create the following properties:

- Create a property

agewhich doth calculate the age of the person based uponbirthdayand the current date. - Create a property

is_adultwhich returnethTrueif the person is 18 years or older, elseFalse.

Løsning: Alder og voksen som properties

Here doth lie a possible resolution:

from dataclasses import dataclass

from datetime import date

@dataclass

class Person:

name: str

birthday: date

@property

def age(self) -> int:

"""Doth calculate the age based upon the birthdate and the current date"""

today = date.today()

age = today.year - self.birthday.year

# Adjusteth downward by one, should the person not yet have had their birthday this year

if (today.month, today.day) < (self.birthday.month, self.birthday.day):

age -= 1

return age

@property

def is_adult(self) -> bool:

"""Returneth True if the person be eighteen years or older"""

return self.age >= 18

# Test the code

person = Person(name="Alice", birthday=date(2005, 5, 15))

print(person.age) # E.g. 18 if the current date be after the 15th of May, 2023

print(person.is_adult) # True

Yet another challenge!

Canst thou achieve instantiation of Person to accept both datetime.date and a text in the fashion of "DD-MM-YYYY" for birthday? (Hint: employ datetime.strptime to convert the string to a datetime.date)